Just as last week we occupied ourselves with "doing audio," which more or less meant writing about music, our concept of "doing video" today will focus mostly on writing about film (and to a lesser degree, television), though it could encompass a far wider range of topics, from cartoons and video games to music videos, YouTube clips, and even GIFs. Still, the ideas and techniques employed in our readings below could just as easily apply to those other disparate media.

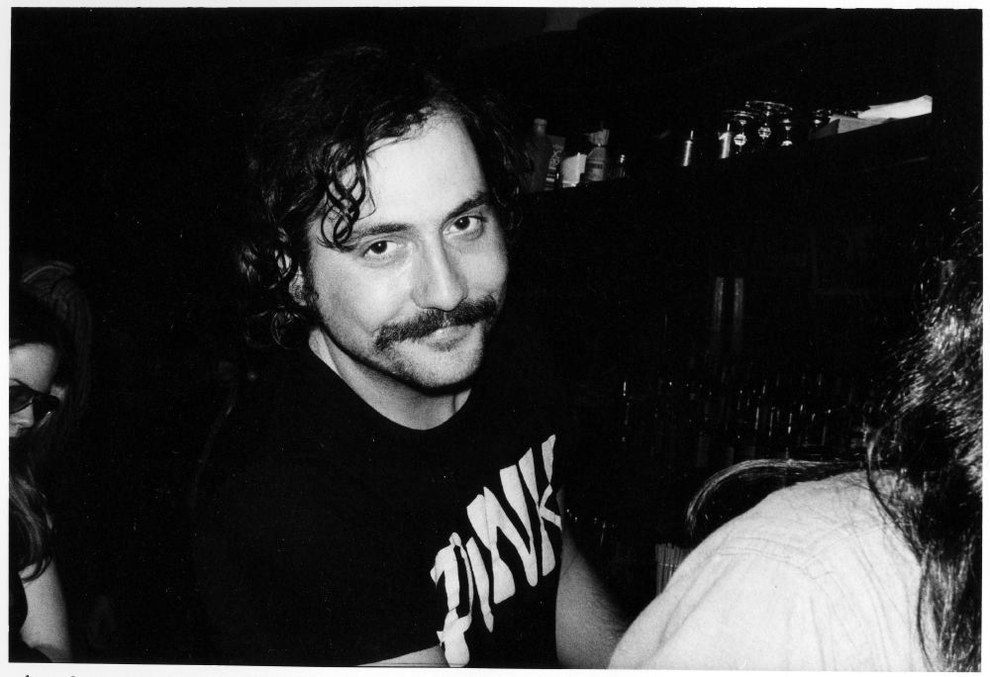

In terms of film criticism, there's perhaps no more esteemed figure than the late Roger Ebert (above), who practically revolutionized the field, along with colleague Gene Siskel, through

their popular eponymous television show. Folks who tuned in on any given week could hear serious, well-considered (if often disagreeing) viewpoints on contemporary movies — from the finest new releases to mainstream dreck — and be exposed to independent productions, foreign films, and cinema classics that might not get coverage in their daily newspapers (though both Siskel and Ebert wrote for competing Chicago newspapers for much of their careers). The good-natured competition between them, along with their passionate perspectives, often resulted in compelling television, and off-screen they could be even more lovingly vicious:

We'll start with one of Ebert's favorite films of all time, and then move on to a few more recent films that you might be familiar with. In most cases, I've linked both his original review and a later analysis for his "Great Movies" series:

Even Ebert's most scathing reviews are fine examples of critical writing and perhaps even more so than his praise for classic films reveal the depths of his love and respect for the medium. Here are two of his most infamous pans. You don't necessarily need to read these, but it is quite pleasurable to do so:

- North (1994) [link]

- Baby Geniuses (1999) [link]

|

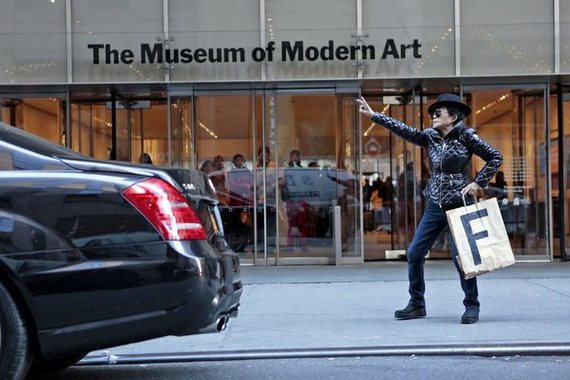

| Pauline Kael at The New Yorker in 1985. |

Aside from Gene Siskel, one of Roger Ebert's few true peers was Pauline Kael,

The New Yorker's film critic from 1968–1991. Kael's highly individual voice — frank and brazen, while unapologetically passionate about films that deeply moved her — won her as many enemies as friends, and while her tenure was relatively brief (she retired after twenty-three years due to Parkinson's disease), her influence was long-lasting, most notably through the "Paulettes." This group of young critics that Kael took under her wing in the 1970s (including A.O. Scott, Elvis Mitchell, David Edelstein, and the two men who'd take her place at

The New Yorker, Anthony Lane and David Denby) continue in her footsteps to this day.

We'll look at a few pieces from throughout her career that vary in length and tone, from French New Wave and American Auteur to one of Scorcese's earliest masterpieces and Dustin Hoffman in drag:

- Masculin Féminin (1966) [link]

- Bonnie and Clyde (1968) [PDF]

- Raging Bull (1980) [PDF]

- Tootsie (1982) [PDF]

Of course, while the film critic has long been held in high esteem, her peers writing on the small screen have not always received the same respect. Nonetheless, just as we find ourselves overwhelmed by excellent scripted television choices in this day and age, a new class of insightful critics have risen to the challenge of writing about this unique medium. While we don't have the time to cover their work as thoroughly, I'd like to offer up a few interesting examples, and also happily point you towards (as an optional read) Matt Zoller Seitz's article

"There Has Never Been a Better Time for TV Criticism" in

Vulture, which highlights some of the very best writers in this field.

Let's begin with Emily Nussbaum, The New Yorker's television critic. Given the high-profile nature of that role, I found her recent reversal of opinion on the Cinemax series The Knick, to be a refreshing act of critical transparency that also made clear some of the challenges TV writers face vs. their film reviewer peers:

- "Surgical Strikeout: Steven Soderbergh's Disappointing 'The Knick'" (8/11/14) [link]

- "I Changed My Mind About 'The Knick'" (10/2/14) [link]

Next, I thought I'd offer up two contemporaneous articles covering very similar ground: the topic of race on one of my favorite recent TV series, 30 Rock. Given the disparate profiles of the two venues and the authors' individual styles, there's as much in common between these pieces as there are differences:

- Wesley Morris, "30 Rock Landed on Us: Identity Politics and NBC's Most Subversive Show" in Grantland (1/31/13) [link]

- Alyssa Rosenberg, "Liz Lemon's White Guilt, The Black Crusaders, and Grizz and Dot Com: Why '30 Rock' Mattered On Race" in ThinkProgress (1/29/13) [link]

Finally, because writing about the moving image can imply more than film or television, I'm also giving you two 2012 pieces by Daniel Zalewski from The New Yorker on Christian Marclay's 2010 installation/film The Clock (you can view an excerpt from The Clock above):

- "The Hours" [link]

- "Night Shift with 'The Clock'" [link]

º º º