Before we get to today's readings I'd like to you take a little quiz. Specifically, the New York Times regional dialect quiz — based on the decade-old work of linguistics researchers Bert Vaux and Scott Golder — which went viral in late 2013 thanks to a novel presentation in a quiz format and some well-constructed heat maps that allowed users to drill down to local variations in speech. Given that we probably have some level of geographic variety in our class composition this should be a good way for you to start thinking about the relative flexibility of day-to-day speech conventions that we take for granted as absolute.

|

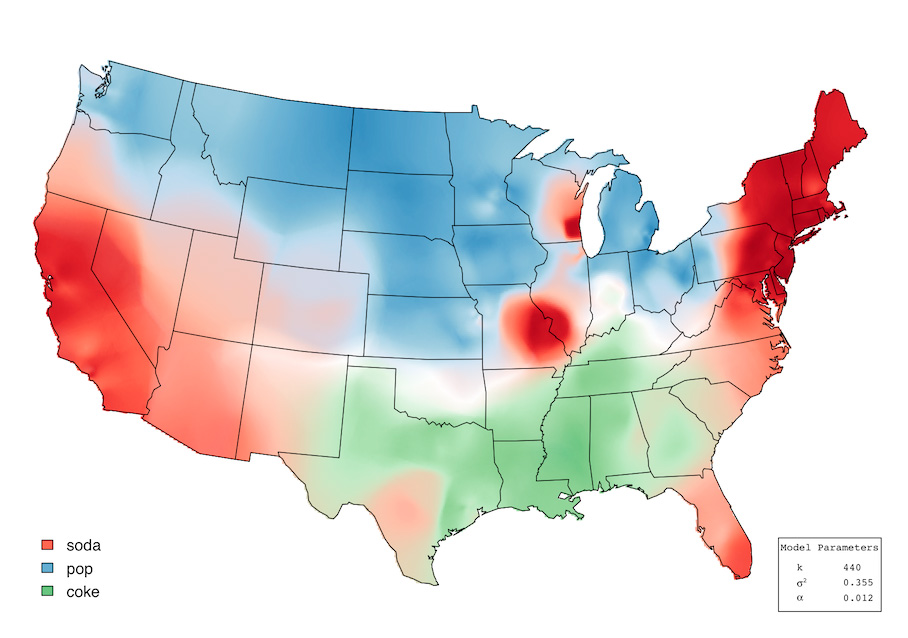

| Regional differences in the term used for soft drinks. |

That linguistic variability is intimately tied to our sense of English as a uniquely mutable and evolving language, and that's certainly not a new idea, as we discover when reading Walt Whitman's 1885 essay, "Slang in America" [PDF], which extends ideas present in his poetry from the very beginning (recall Whitman published Leaves of Grass with a brief glossary explaining to unfamiliar readers what terms like "pismire," "Paumanok," "Tuckahoe," and "quahog" meant).

This appreciation of regional and temporal variability frequently yields modern-day listicles like Slate's recent "The United Slang of America," The Guardian's "Basic Question: Did Sylvia Plath Write Like a 21st-Century Teenager?," "These Words You Use Every Day Have Racist/Prejudiced Pasts, And You Had No Idea" from The Huffington Post, and NPR's "16 'Spiffy' Words College Students Used in 1916," and certainly, pop-cultural pieces like that point us in the right direction of thinking more objectively about the origins and uses of language.

Still, these pieces aren't quite as critically robust as we might wish they were. I'd like to point out two examples of entities doing great ongoing writing about words and their history and use. First, from Slate's excellent "Lexicon Valley" column, here are a few recent articles:

Next, NPR's wonderful "Code Switch" column, which explores the "frontiers of race, culture, and ethnicity," has an occasional feature entitled "Word Watch," which offers up well-researched analyses of the racially-charged language we might not even realize surrounds us. A few examples from "Word Watch":

Still, these pieces aren't quite as critically robust as we might wish they were. I'd like to point out two examples of entities doing great ongoing writing about words and their history and use. First, from Slate's excellent "Lexicon Valley" column, here are a few recent articles:

- Jacob Brogan, "What is the F--kboy?" [link] (as promised on day one)

- Katy Waldman, "When Did Feminism Get So 'Sneaky'?" [link]

- Katy Waldman, "The Incredible Shrinking Zeitgeist: How Did This Great Word Lose Its Meaning?" [link]

- Katy Waldman, "Why We Be Loving the Habitual Be" [link]

Next, NPR's wonderful "Code Switch" column, which explores the "frontiers of race, culture, and ethnicity," has an occasional feature entitled "Word Watch," which offers up well-researched analyses of the racially-charged language we might not even realize surrounds us. A few examples from "Word Watch":

So how might you try to do this sort of etymological writing on your own? First take stock of the techniques and approaches that the writers above have used — remember, good writers cite their sources so that you can follow their bread crumb trail. Dictionaries — whether hard copy or online; as august an institution as the OED or as wonderfully crass and spontaneous as Urban Dictionary — are your best friends, and even basic Google searches will often reveal the complicated histories and origins of words.

That notwithstanding, much of the power and identity of individual words lies (as our examples show) in their day-to-day use and their evolution over time. Aside from finding specific examples from books, magazines, newspapers, and other media, one of the more useful tools at your disposal is Google's powerful Ngram viewer, which allows you to trace trends in usage in books over time from 1800 to 2000 (using the complete corpus of Google Books' archives) and make conclusions about what influences those trends. Here, for example, we can see the use of "Dylan" as it gets a boost from Dylan Thomas in the 1950s, a bigger boost from Bob Dylan in the 60s into the 70s, and then become the name of at least seven kids in your eighth grade class:

For more recent queries — from 2004 to the present — accounting for web traffic vs. appearances in books and other printed media indexed in Google Books you can use Google Trends to track interest over time, regional interest, and related search terms. Here, for example, you can see Google traffic surrounding the search term "Sam Dubose" over the last 90 days:

No comments:

Post a Comment